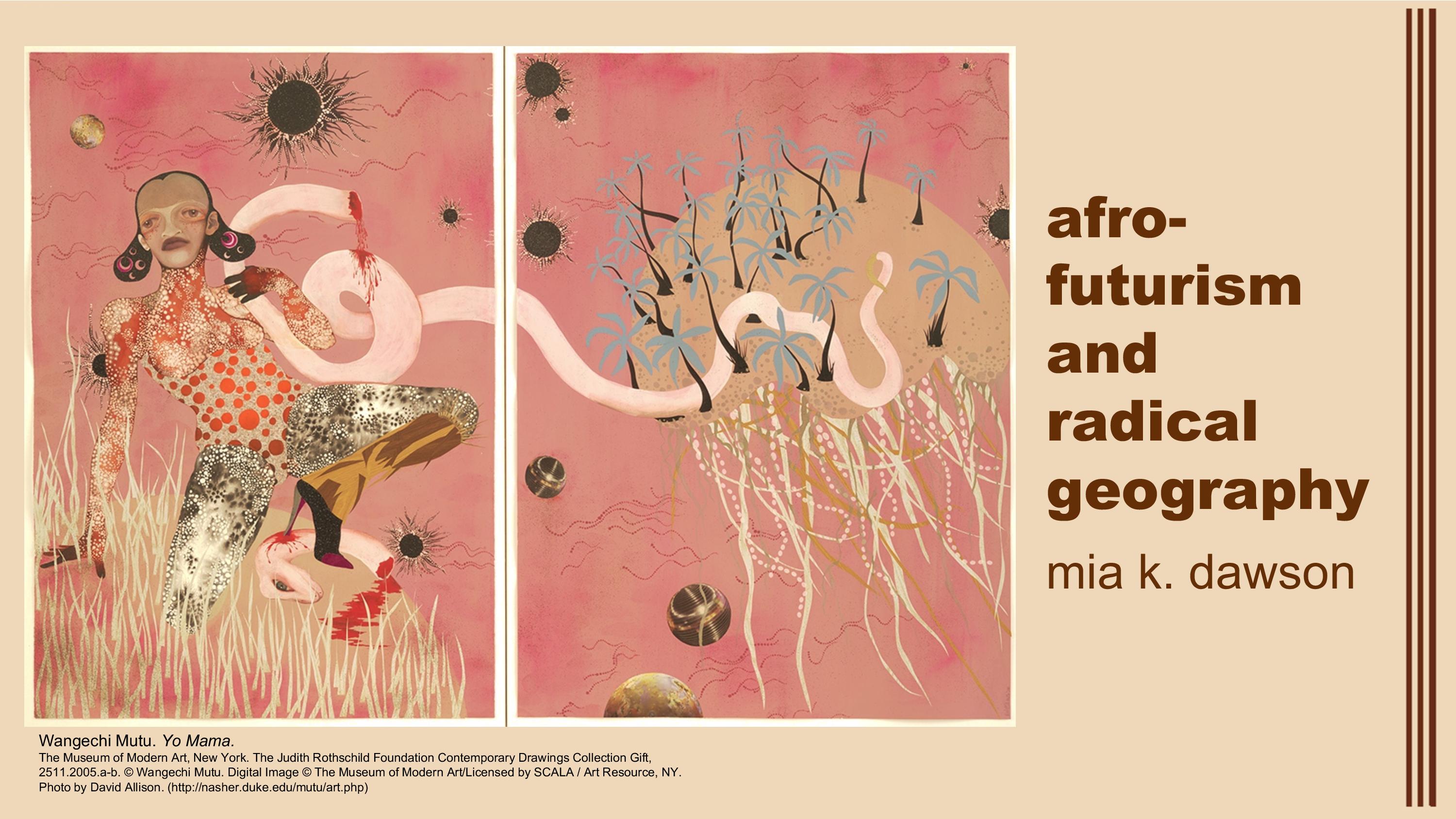

This post is an adaptation of the slides and narration from an October 12 pecha kucha presentation at the 2017 Imagining America conference at UC Davis. The pecha kucha format involves showing 20 slides for about 20 seconds each for a 7 minute presentation to encapsulate an idea. The idea that I hoped to communicate here is that afro-futurist aesthetics can help us envision and develop mapping technology towards black liberation.

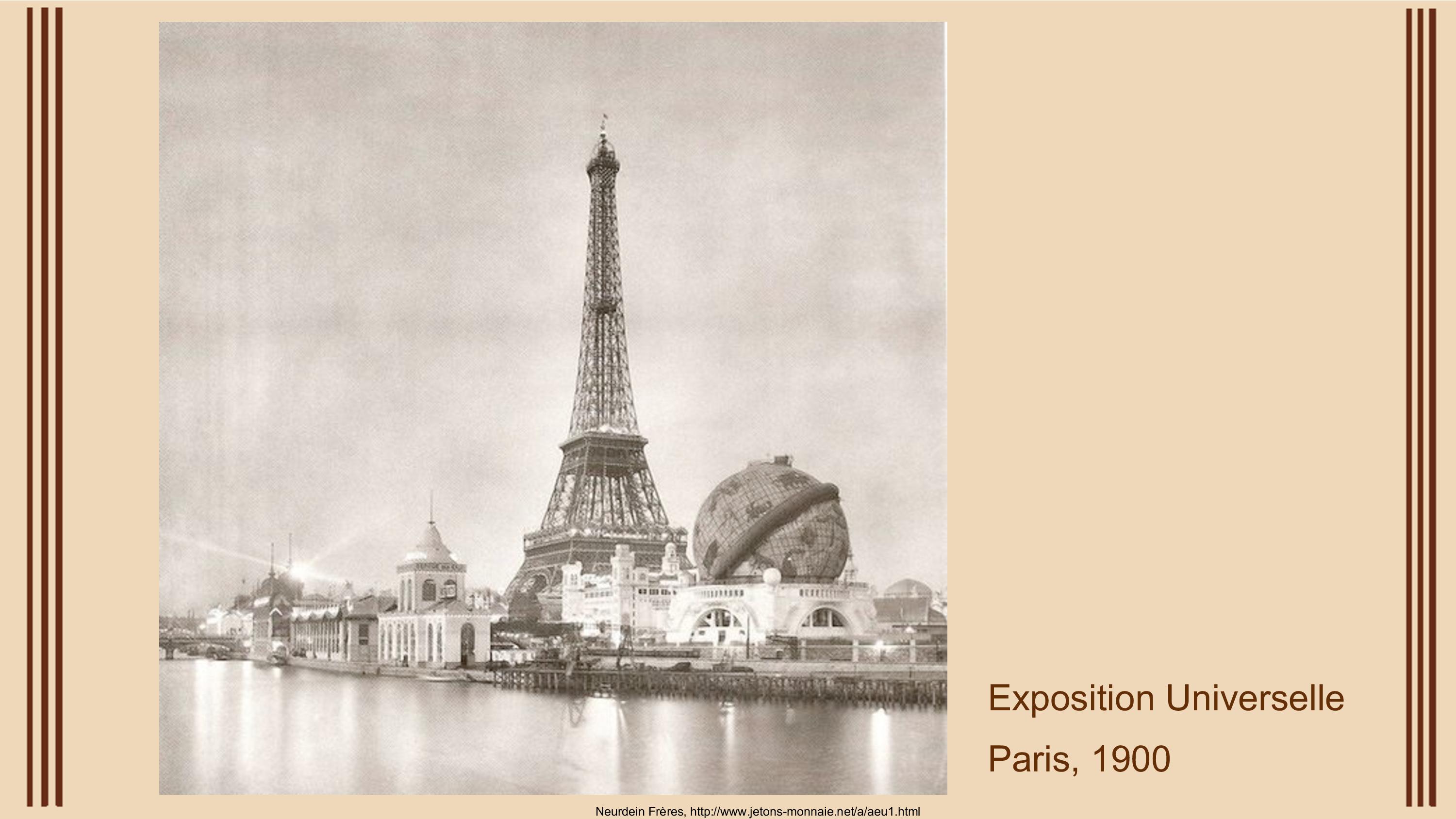

I’m going to start off with a story that takes place at the exposition universelle or “world’s fair” in Paris in 1900. This gathering was meant to celebrate Europe’s achievements of the nineteenth century and to spur their advancement into the twentieth century. In the year 1900, European colonization of the globe was reaching a zenith. The scramble for Africa among European powers was in full swing. A large part of the mission of fairs like the exposition universelle was to celebrate the material gains made possible by colonization and to gain popular favor for its continuation.

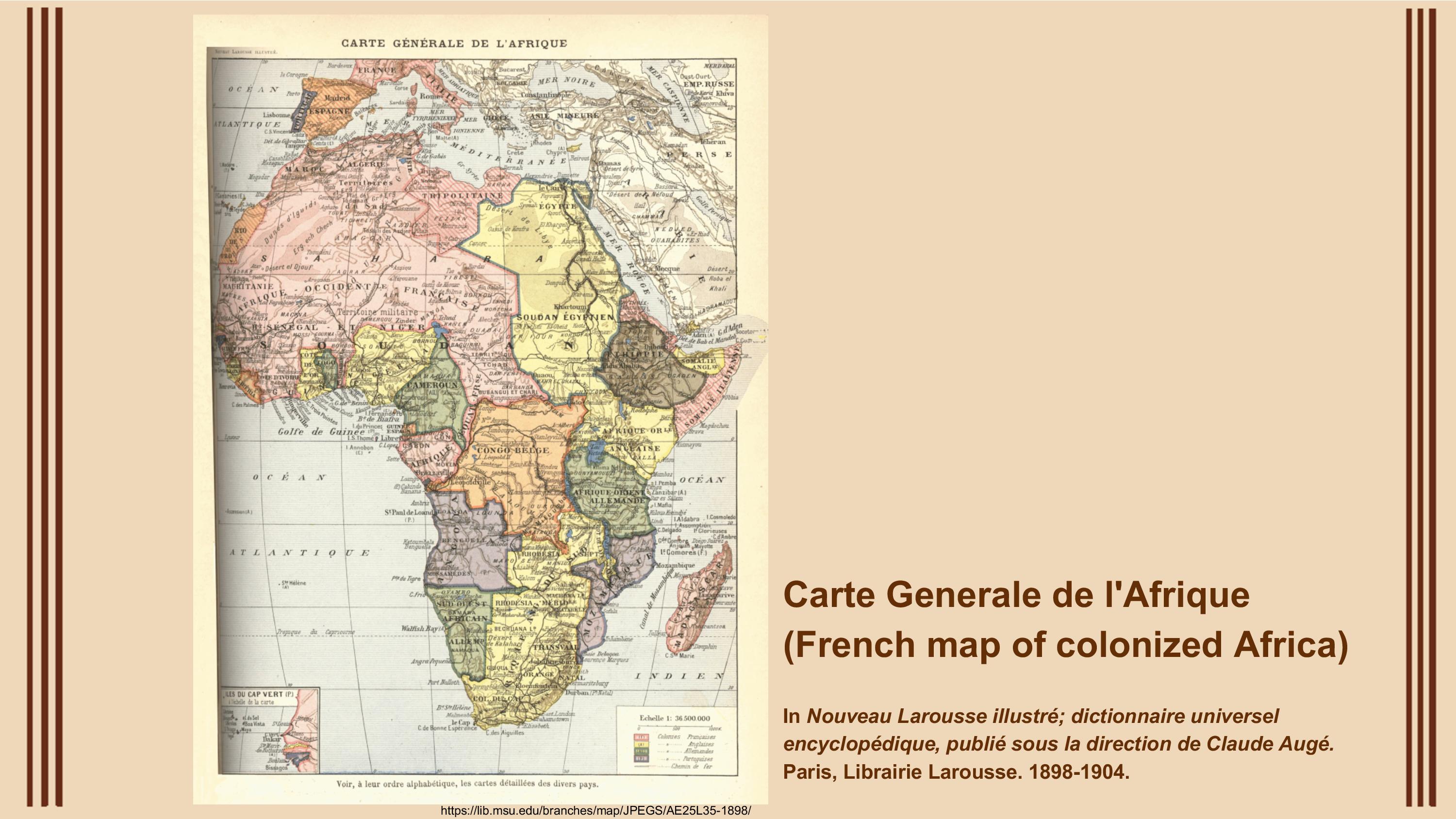

At this time, Western scientific thought was engaged in a concerted effort to organize humanity into discreet, hierarchically organized races. Western biology, anthropology, and geography were all in lockstep in their work to naturalize white supremacy. Many geographers at this time subscribed to a theory of environmental determinism, which held that tropical climates led to the development of lethargic, degenerate, and uncivilized races.

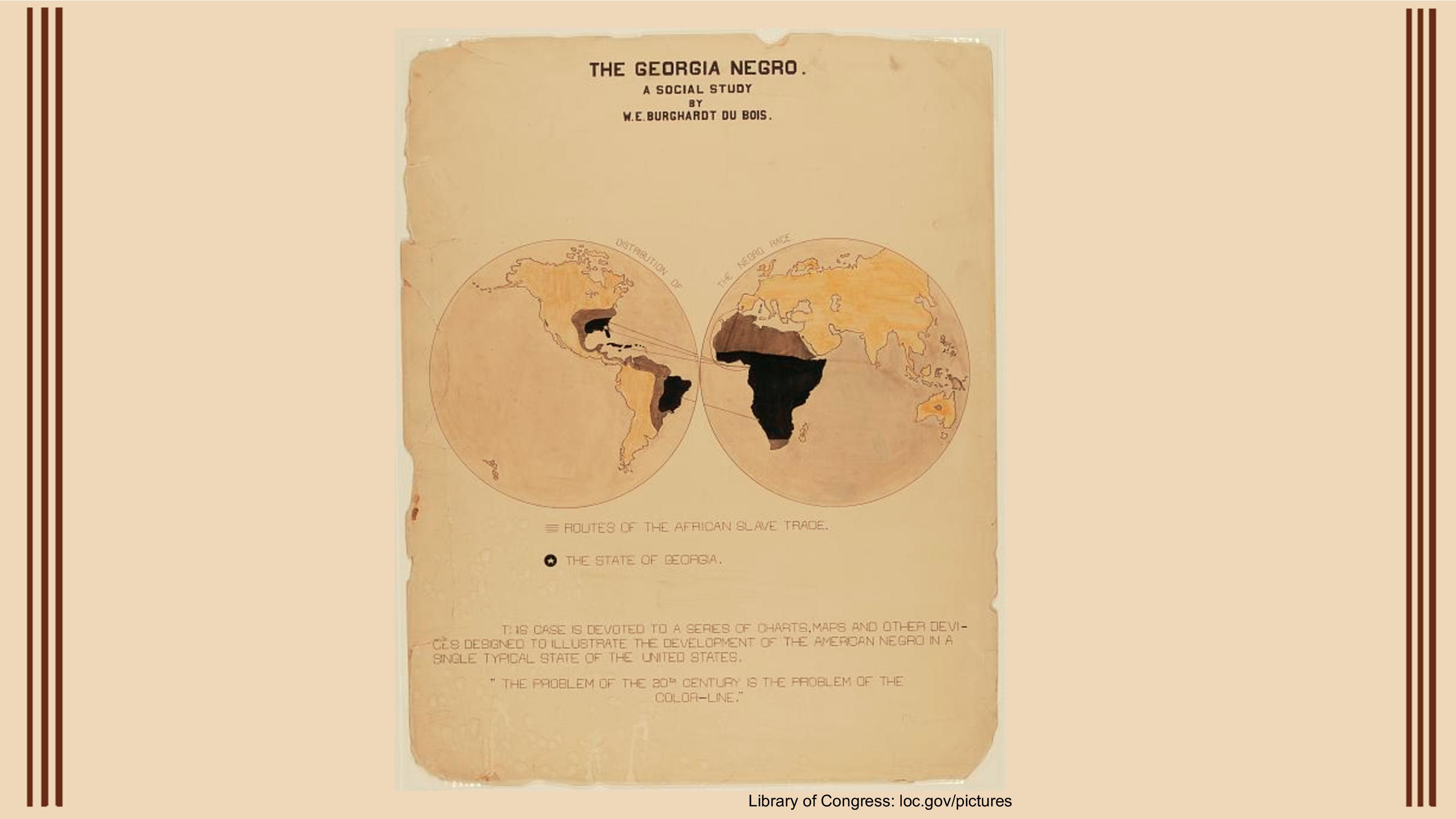

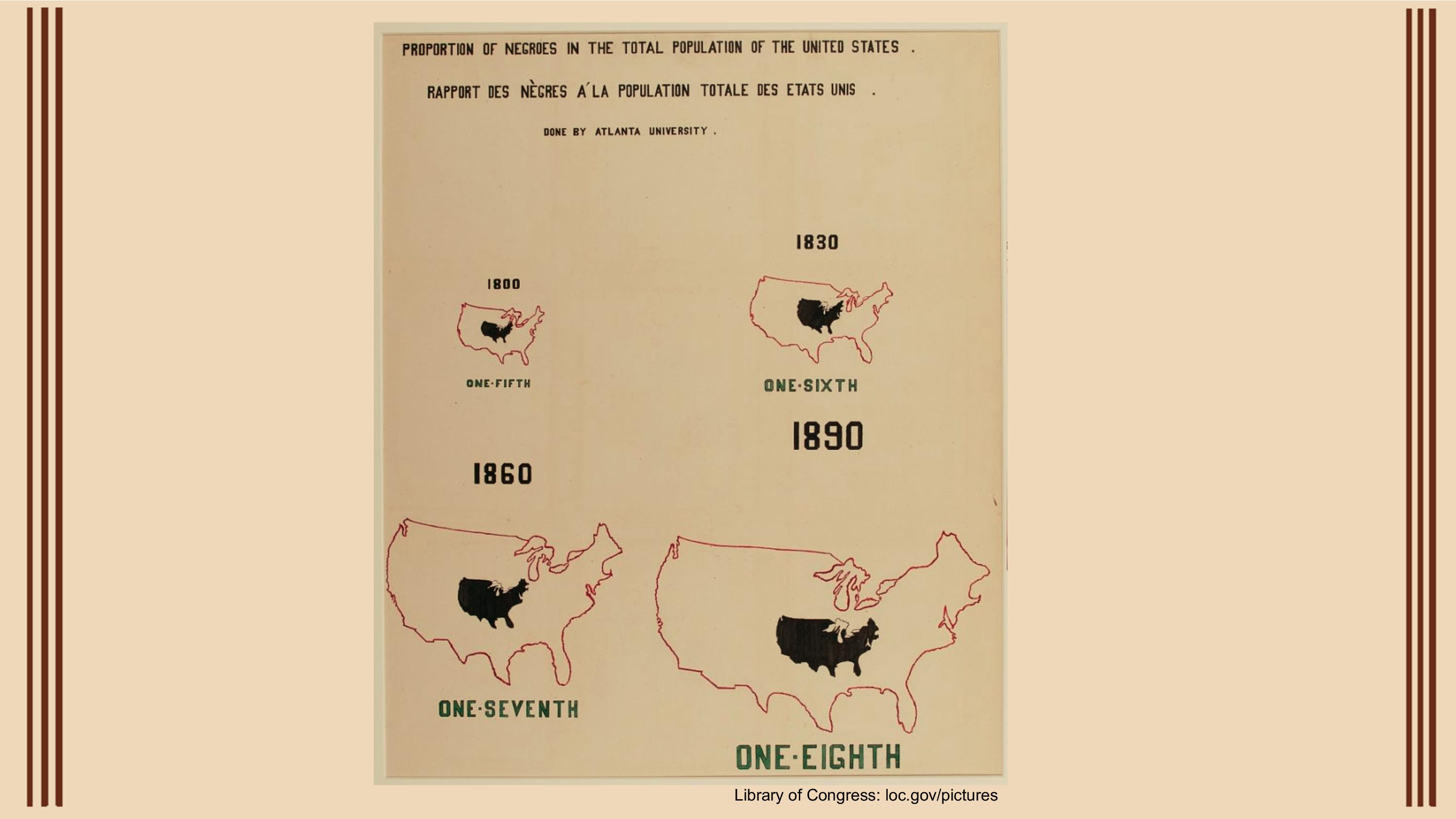

W.E.B. DuBois was called upon to organize an exhibit to depict the lives of people of African descent in the United States at this fair. It was his aim to depict the rapid advancement of his people since the emancipation proclamation less than fifty years prior and to make a case for the intellectual equality of black people to whites. He was given a rare opportunity, as a black person, to speak for his own race in a time and place where virulent anti-black racism was the social norm. Depictions of colonized subjects in other exhibitions at this world fair were deeply violent and dehumanizing, including human zoos where Africans were confined for spectacle.

On a crunched timeline of just four months, DuBois and his students set out to research and compile information for an exhibit. This map, which served as the cover for the study, shows the routes of the trans Atlantic slave trade. The caption reads: “this case is devoted to a series of charts, maps, and other devises designed to illustrate the development of the American Negro in a single typical state of the United States.” And then it states: “The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color-line”.

That prediction has become famous in African American studies, and is widely considered to be prophetic.

DuBois’s maps, and the story behind them, can help illuminate some of the central ideas of radical geography. Radical geographers recognize and deal explicitly with the power of maps. Let’s bring this back to the twenty first century. Have any of you ever had your GPS tell you turn the wrong way on a one-way street? Did you follow it? This happens all the time. And this is a dramatic illustration of the power of maps. The map had become more real to you in that moment than the territory you could see with your own eyes. This is just one small example of how maps can dictate how we perceive our landscape.

In other words, all maps tell stories. When we make maps, we codify our subjective views of a landscape. These views then influence those who use our maps by shaping their perception of the world. This feedback loop between maps and worldviews is exemplified by the way we tend to think about political borders. Political borders are immaterial, and they have changed dramatically over the centuries; in most of the world, current borders have been imposed relatively recently by outside, colonial powers. But we see these lines on almost every map we encounter, and we believe deeply in them; we generally imagine them to be set in stone.

There are several questions that can help us dig in to the story that a map tells. What is being mapped? Who does the mapping, and for what purpose? How are they funded? Using the example of DuBois at the Paris Exposition: DuBois mapped black life at the turn of the century. He was funded by Congress. DuBois’s own aims were assuredly more radical than his funders. While DuBois wanted to show the achievements of black Americans and make a case for their equality, the administration most likely wanted to promote American nationalism by putting forth the idea that the country had absolved itself of the sins of slavery. The maps that he produced probably represent a compromise between these competing goals.

Today, we also have to ask ourselves what technology we are using, and what are its implications. Geography is an increasingly technological field, and radical geographers must ask who has control of these technologies, and to what ends they will be used. This brings us to our conversation about afro-futurism.

Afro-futurism is a powerful aesthetic that can help radical geographers conceptualize the possibilities and limitations of using geographic technology towards black liberation. This aesthetic grapples with the relationship between blackness and Western science and technology. The relationship is complicated and troubled: Western science has falsely justified our supposed inferiority, has used us inhumanely as test subjects, and has largely excluded us from participating in its knowledge production. When we have gained entry to the halls of science, our achievements have been under-recognized and suppressed in disciplinary histories.

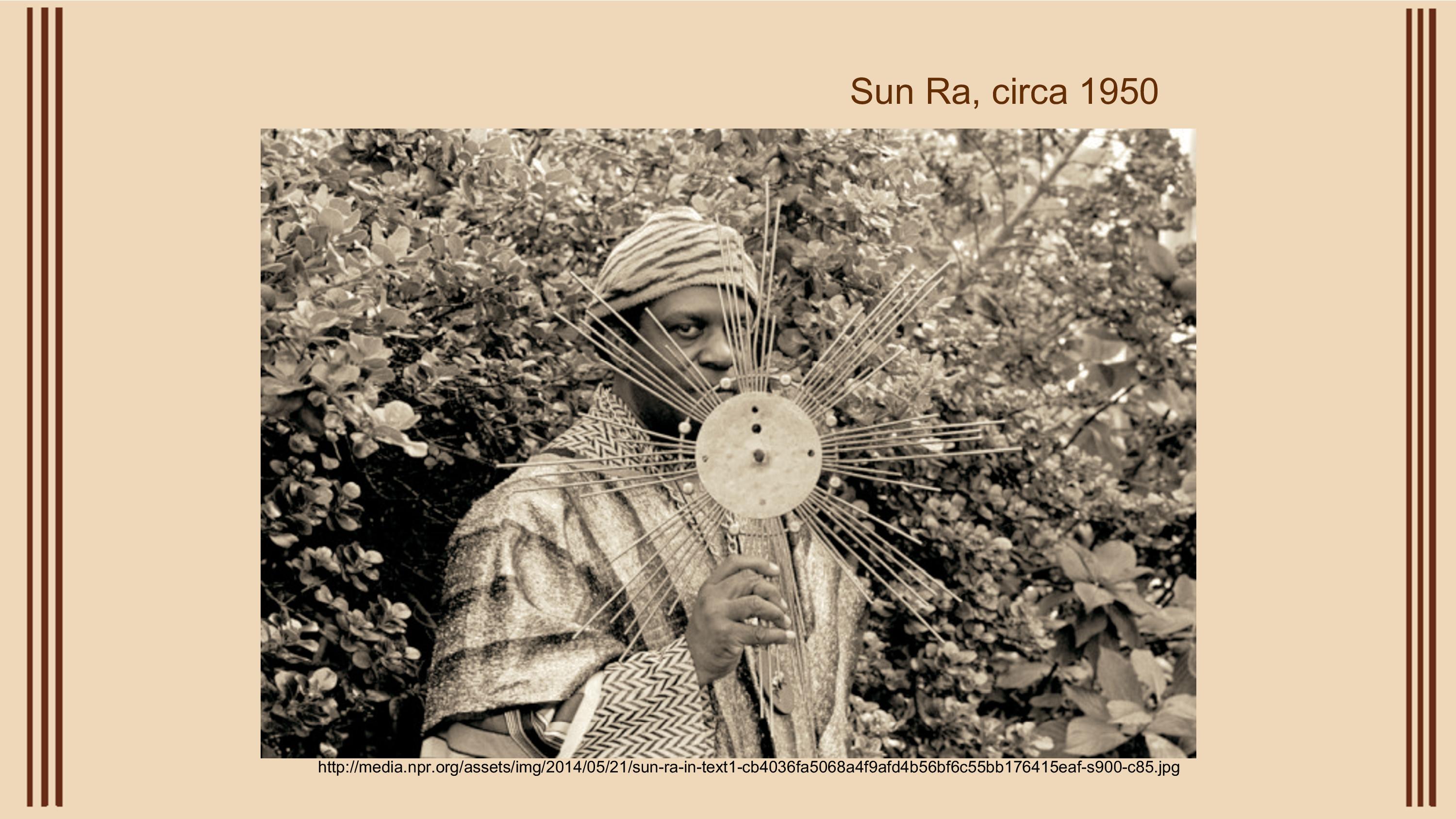

Afro-futurism is an aesthetic that can help us envision new possibilities where blackness, science, and technology, intersect. Sun Ra was an early artist to develop this aesthetic throughout a long career from the 1930s to 1990s. Sun Ra and other artists within the tradition use imagery associated with science fiction, fantasy, and magical realism, to bring attention to contradictions of modernity and to connect blackness to a larger cosmos.

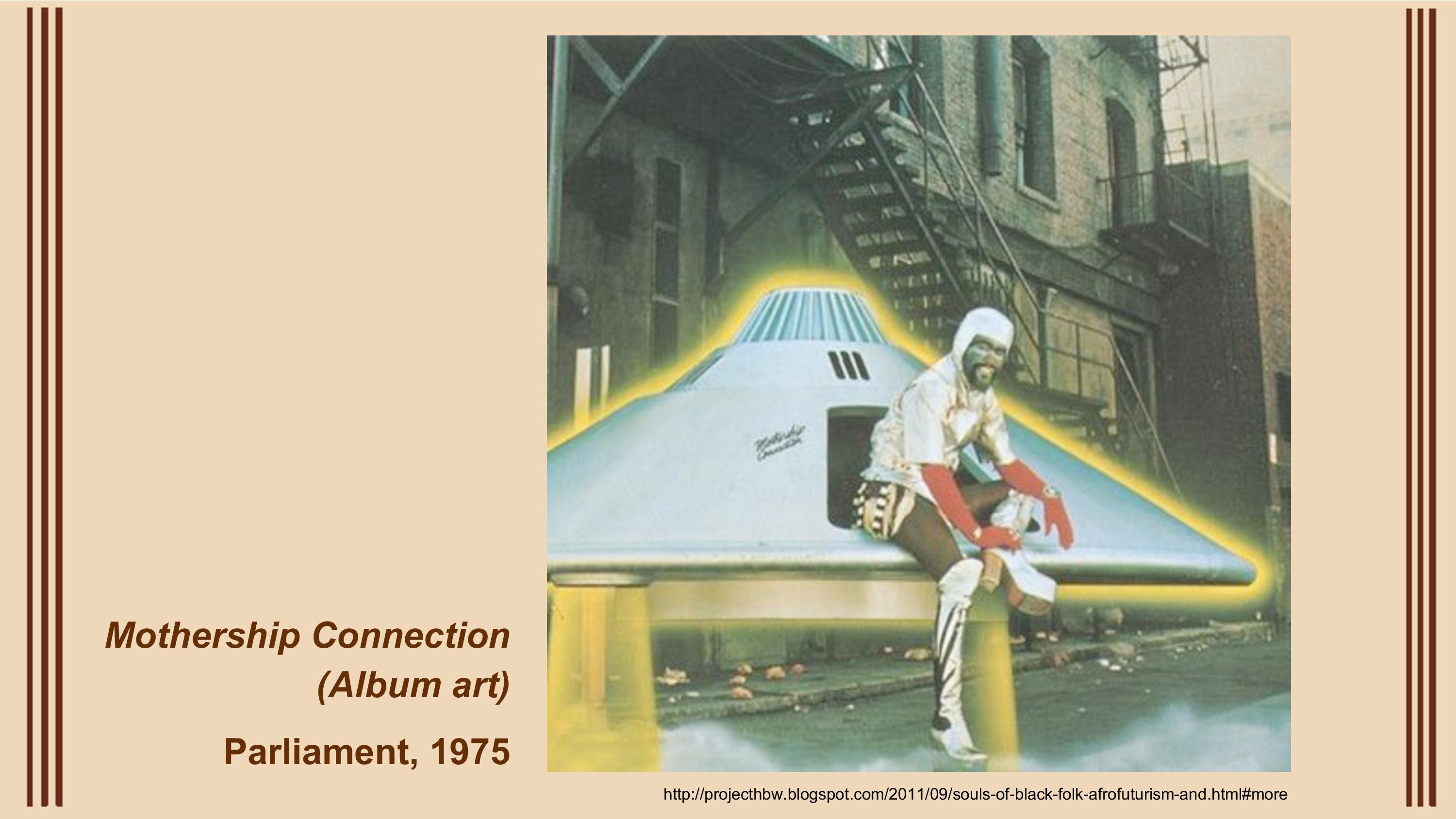

Parliament and Funkadelic are two bands whose influence on the aftro-futurist aesthetic would be difficult to overestimate. Taking inspiration from the soul of James Brown, the rock of Jimi Hendrix, and the radical political commentary of Gil Scott Heron, this large group of artists embarked on a journey that would take black popular music in an entirely new direction. The new genre that they helped forge – funk – drew on new technology such as synthesizers and auto-tuning.

This use of digital technology in their music was paired with visual aesthetics that put blackness in proximity to science and technology, often drawing from comic books for inspiration. In their imaginative landscapes, new technologies harnessed and unleashed by “the funk” would free black people, and the United States as a whole, from a state of violence and despair.

Hip-hop evolved out of funk as a new form of expression for black America, and taking inspiration for their predecessors, many hip-hop artists have embraced afro-futurist aesthetics. OutKast delve into the experience of blackness as a type of alienness in mainstream society on this classic album.

Artists in the afro-futurist tradition encourage us to approach science and technology critically. By placing the narratives of oppression and disillusionment in proximity to science and technology, they complicate our notions of progress and modernity. As such, these artists articulate and engage with the many of the ideas that radical geographers grapple with, and identify new directions for our thinking.

My project using open-source data and software to map police killings in the U.S. has led me to this exploration of the tensions between geographic technology and the black experience. What is the role of data and mapping technology in the fight for black liberation? Artists in the afro-futurist aesthetic, through their work to articulate varied relationships between blackness, science, and technology, can point us towards an answer.

#JUSTICE4ADRIENELUDD

#JUSTICE4JOSEPHMANN

#JUSTICE4LORENZOCRUZ

#JUSTICE4DESMONDPHILLIPS

#JUSTICE4MIKELMCINTYRE

#JUSTICE4DAZIONFLENAUGH

#JUSTICE4RYANELLIS

#JUSTICE4JAMESNELSON

Works cited

Bell, Pedro. Cover art for Funkadelic, 1978, One Nation Under A Groove. Warner Bros., Burbank, CA, USA.

EMEKx. Cover art for Erykah Badu, 2016, But You Caint Use My Phone. Motown, Detroit, USA.

Gomez, Frank. Cover art for Outkast, 1996, ATLiens. LaFace, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Gribbitt! Cover art for Parliament, 1975, The mothership connection. Casablanca Records, New York, NY, USA.

Mutu, Wangechi. Yo Mama. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, USA.

Provenzo, Eugene F., Jr. 2013. W.E.B. DuBois’s Exhibit of American Negroes: African Americans at the turn of the century. Roman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD, USA.